Some Uses of Photography: Four Washington Artists at American University’s Katzen Arts Center is a unique kind of photography show. In a dark room tucked away on the third level is an intriguing exploration of how photography is used to make art. I was delighted to see that Phyllis Rosenzweig, a former curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, organized the exhibition—she was, big disclaimer, one of my thesis advisors, so I asked to interview her about the exhibition and how it serves to change the dialogue of cataloguing photography in contemporary art.

We met up at the Hirshhorn and decided to walk to the National Gallery sculpture garden—a lovely place to discuss art. I asked Rosenzweig how she first conceived the show. She had been frustrated no longer working in a museum, so she approached director and curator of the Katzen Arts Center, Jack Rasmussen, about organizing an exhibition. She brought him a folder filled with samples from her favorite artists over the years. He said to her, “You seem to be very interested in photography.”

Three years ago, when the meeting took place, Rasmussen wasn’t interested in exhibiting solo shows. Since many of the artists Rosenzweig admired were women, they began discussing an all-woman photographers show, and planned the show to coincide with the 2014 Feminist Art History Conference at the Katzen Arts Center—where three of the four the artists will be speaking. However, Rosenzweig asserts that this is not a show primarily about a feminist esthetic.

She finally selected four artists, Jenn DePalma, Ding Ren, Siobhan Rigg, and Sandra Rottman because she thought that “they would look great together. I thought the show would be about four people whose work I really like, and exhibit the variety of approaches to photography—a small sampling of what photography can do.”

Rosenzweig wanted to understand how these women use photography—only Ren and Rottman self-identify as photographers. Ren creates ethereal images that depict reoccurring natural patterns and architectural forms like windows, doors—“portals”—that she observed during a nomadic period in her life. The exhibition features her uses of analogue photographic practices—color film, dark room processing, and a slide projector—a disappearing technique of photography that is being conquered by artificial filters to make digital photography look like film.

Rottman uses photography as visual documentation, recording her niece’s evolution since birth. Rosenzweig says the artist’s “images document true moments that are posed and performed for the camera. [They] join the debate about the position of photography in today’s contemporary world.”

DePalma and Rigg, on the other hand, use photography as a found or made material. “Their work is not about the craft of photography per se,” Rosenzweig says. “They are involved in those things, but would not consider themselves photographers. This has been a long time discussion about contemporary photography and what exactly is photography in the digital age.”

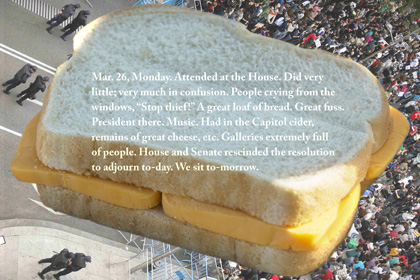

Rigg juxtaposes both found images and photographs she takes with text, performances, and other media to explore a series of events involving large items: the discovery of mammoth bones in New York, and the gift to the White House of a giant, 1,234 pound block cheese from the residents of Cheshire, Massachusetts and a riotous party held by the Senate. Rigg responds to these events by comparing contemporary large events such as the Keystone XL Pipeline protests and the concept of organizations being “too big to fail.” Rigg uses photography as supplemental material to demonstrate a larger historical relationship between trans-generational political agendas.

We began to discuss photography and its context within contemporary art. I ask what her thoughts are about photography as a medium, and what the uses of photography mean in contemporary art. Rosenzweig says, “It’s a complicated issue because I think there are still two camps.” The first camp are artists, curators, and writers who see photography as its own identity. These people call themselves photographers, curators of photography, photography writers. The second camp are people who see a greater fluidity in the medium of photography. They are using photography as a way to explore broader conceptual ideas. They are artists–who do not consider themselves photographers–using photography as a tool to help exhibit, either their process or final concept.

She continues, “That’s a different trajectory sometimes from artists who are maybe more conceptual. They are not focused on using a specific material. They are more interested in investigative and philosophical or intellectual questions. It’s very odd right now. Curators really discuss and argue about this. And there have been a lot of questions about ‘what is photography?’ I suspect that some photographers would come to this show and think that this has nothing to do with photography.”

Some of the artists, mainly Rigg and DePalma, use photography as an instrument to make other types of art. Rosenzweig agrees, “What strikes me as interesting is, I think that photography is a peculiar mode of expression, in a sense, that since its beginning—since it was invented—people always asked is ‘it art or is it not?’ but there is not history of saying, ‘I use paint, I use ground up pigments and mixed in is something that holds it all together,’ and no one says, ‘Is paint art?’ It was always an interesting question to me, and the problematic status of photography and its unique categories of what we consider art.”

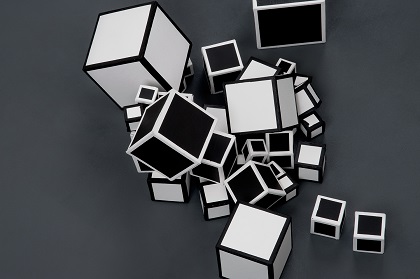

For instance, in 17 Cubes, which Jenn DePalma conceived, constructed and painted 17 black and white cardboard boxes of varying sizes, then slipped the cubes down a tube tumbling to a flat surface. She calls the random configurations in which the cubes land a still-life. She had a colleague photograph the still-life, and DePalma made graphite drawings of the images. DePalma was “hoping to add value to the photography,” says Rosenzweing. “The copy of the original photograph looks like a drawing and the drawings look like photographs.” DePalma isn’t concerned that the photographs or drawings represent the identity of a medium but challenges the capacity of how a medium operates—alone or juxtaposed with other media.

Rosenzweig discusses the complexity of DePalma’s project, “It’s another kind of wrinkle—she’s not the photographer and she’s not the video-maker, but it’s her idea. She had these crazy systems that really amaze me.”

I mention that it seems inspired by Sol LeWitt. “Yes!,” she says. “It was so enormously painstaking and time consuming to make the cubes—something you would think she would have someone make for her. And then the drawing—it was the same thing. They were very Sol LeWitt—taping all the edges, working on sections at a time, and it’s incredible.”

Exhibiting the diverse works and uses of photography by DePalma, Ren, Rigg, and Rottman promote more questions and inquires about the photographic medium–it’s perhaps most telling that Some Uses of Photography needs to be labeled as a photography exhibition for the much of the work within it to be considered to be photography.

Some Uses of Photography: Four Washington Artists is on view through December 14th at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, 4400 Massachusetts Ave NW, Washington, DC 20016. Admission is free. Tuesday through Sunday, 11am-4pm.

The 2014 Feminist Art History Conference, American University, Katzen Art Center, October 31 – November 2. Gallery Talks with the artists on November 2 at 1-2 p.m.