-

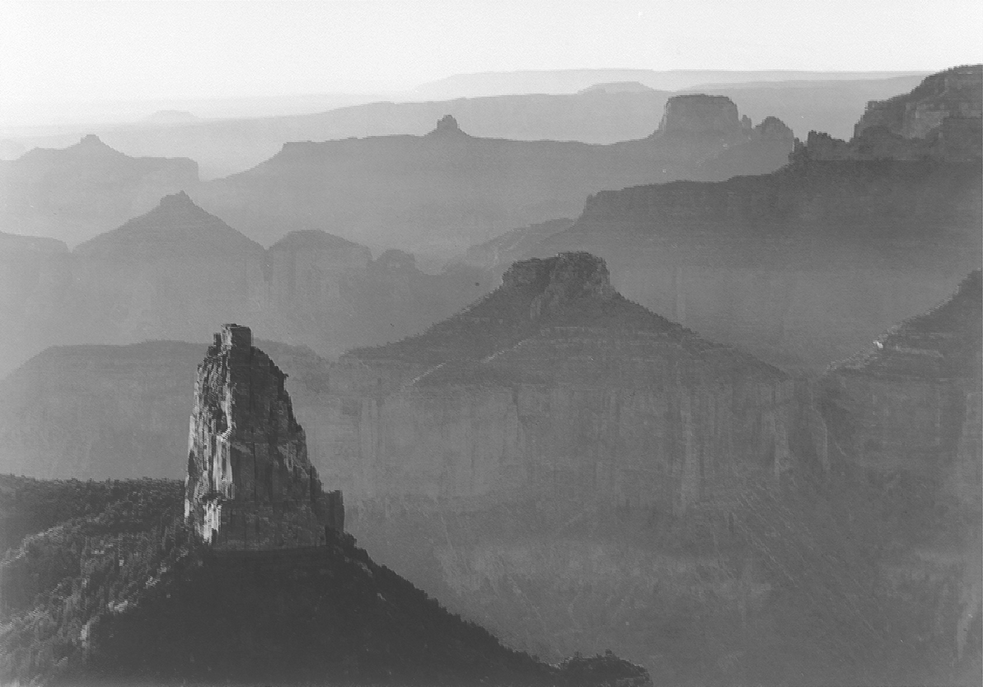

Grand Canyon National Park – Ansel Adams. Part of the Ansel Adams collection at the National Archives.

When we think of photography books, we first think of the hard bound copies of the works of our favorite photographers. It is the pages and pages of images that come to mind because of the way they draw us in. Delving into a photographer’s body of work can be inspiring, can make us think of new ideas, and can transport us into the way that someone else sees the world. Books on photographic theory, and biographies about photographers, provide us with a different insight. We can learn about the approach another photographer takes, or we can appreciate their work in reference to the circumstances of their life.

A few weeks ago local photographer Joshua Yospyn posted a Suggested Reading List on his blog. The twenty-six works that he chose were either theory based or biographical. They range from Susan Sontag’s popular “On Photography” to Timothy Egan’s biography of Edward Curtis. We asked Yospyn about his selections, and he gave us a great analysis of one of the books, “Ansel Adams: An Autobiography.” Yospyn’s passion for the book, and thoughts on Adam’s life, are a great introduction to his list.

My standout on that reading list is Ansel Adams’ hardcover autobiography, published just before he died in 1984. The 400 pages of breezy text are interspersed with over 200 photographs, including not just the artist’s master works, but dozens of candids of himself. You can tell the man was a happy camper: he’s smiling or goofing off in every picture. It’s a lighthearted visual narrative from a master printer known to tackle heavy subjects like the Zone System and the technical mechanics of darkroom photography.

For example, there’s a photograph of him dressed in toga from 1977, a series of hammy portraits his wife Virginia took in 1930, and pictures of him palling around with an aging Imogen Cunningham in the 1960s. There’s even a photo of a handwritten price list for elementary school class pictures that Adams used in 1920. You’ll see numerous photographs of him teaching, working in the darkroom and playing the piano (as a teenager, Ansel rigorously trained as a classical pianist, “Musicians practice constantly; most photographers do not practice enough,” he writes).

But Adams also turned his camera on his friends. There’s a triptych of Dorothea Lange (smiling) on top of a car, Margaret Bourke-White (smiling) with her cat, and entire chapters on his relationships with Edward Weston (smirking), Alfred Stieglitz (smiling), Georgia O’Keeffe (smirking), and Edwin Land (glowering), the inventor of Polaroid film.

Consistent with its jovial mood, the book is full of exclamation points. “Naturally I could get away!” exclaims Adams of an invitation to visit Carmel, Calif. In another chapter he describes using flash powder to photograph a bridal party, “When I fired the gun – Pffuff! –there was a really bright light, and clouds of smoke rolled along the ceiling.” In the process he “hopelessly scorched” a door frame in the room and paid to have it fixed, which “totaled much more than what I got for the pictures.”

There’s no question Adams is confident of his ability and environmental stewardship, but the book is written in self-effacing prose. Of his first meeting with Stieglitz, whom he prefaces as the “greatest photographic leader in the world,” the young Adams entered his New York City gallery with “trepidation” and was “extremely nervous.” On teaching, he was sensitive of the impact his critiques might have on students, “What if Alfred Stieglitz in 1933 had dismissed my work with a shrug?”

Beyond the iconic Modernist, an encounter with Diego Rivera prompted Adams to write that the painter “anticipated several things I had to say seconds before I had summoned the bravery to say them.” On Weston, he confesses, “I was always a bit astonished (and perhaps a little envious) at Edward’s achievements with the female of the species.” On perhaps Adams’ most famous photograph, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, he reflects, “I knew it was special when I released the shutter, but I never anticipated what its reception would be over the decades.”

So many of the photographers on that reading list lost their minds, self-destructed or even committed suicide. But it’s a tired cliché that all the great artists were manically depressed, insular or egomaniacs. According to his own pen, Ansel Adams enjoyed his life immensely (!), benefited from the wisdom of others and has the pictures to prove it. It’s also a testament to the power of living a life deep within the natural world. I will never lose this book.