Looking Out, Looking In at the National Gallery of Art is a small, humble show featuring mid-century artist Andrew Wyeth’s paintings of windows and farmhouses – a show that quickly became one of my all-time favorite exhibits. You will not see his most famous painting, Christina’s World, or images of his muse Helga; instead, the NGA has followed the thread from their painting, Wind from the Sea, which is regularly on view. This is an emotional journey through light, movement, and contemplation—not only in the process of his paintings but the process of where your mind wanders while looking at art. These works felt familiar but I could not unravel the why at first—this is the first I’ve seen most of these works. I looked back and forth between the paintings and their labels—the dates struck me. The 1940s through 70s were not frequented with many ethereal, subject-driven paintings.

However, photography was.

Images of barren, unadulterated landscapes—cities and rural terrains—provided the audience with images they see but don’t normally observe. I blurred my vision to imagine what these paintings would have looked like in black and white. Wyeth’s hallucinatory images—his studies and the finished pieces—washed away the mystery of the familiarity. Wyeth’s images were nestled in my confused memory with photographs from the 20th century.

Lewis Baltz, Walker Evans, and Harry Callahan are very different photographers, yes, but I cannot help but see their photography in Wyeth’s paintings. At first glance, Wyeth’s work appears to be repetitious renderings of windows and farm scenes, but they are presented in diverse visions.

Lewis Baltz’s images show geometrically flattened desolate landscapes. But his careful consideration of the lighting, shadows, and innate introspection turns a photograph that is seemingly void of a subject into a nearly tangible object and moment. In Baltz’s Tract House No. 22, 1971 the viewer gazes through a window that completely allows light to infiltrate it, but finds the inside empty—the view is only the façade of an adjacent home. The windows this home allow no light to penetrate them—there is no conclusion.

Wyeth’s Off at Sea, painted four years after Baltz’s photograph was taken, is a pale and rigid rendering of a porch. Like Baltz’s photograph, the image is created with near mathematic precision. The porch bench and windowpanes join together like pale, fragile bones. A jagged, empty hanger dangles in the upper left corner—emotions brood in the sensation of death. The search for an ending continues from Baltz’s image. Only a hint of hope reflects in the window—canopies of trees attempt to signal an end to the haunting. However, the juxtaposition and bleak colors—wallowing in melancholy—pull you back to the quiet porch.

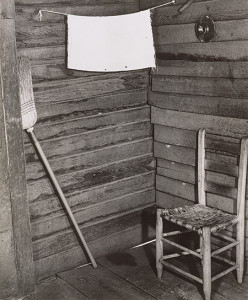

In many of Wyeth’s paintings, I feel the essence of Walker Evans’ America. His scenes of the Great Depression are quintessential visions of American life. Like Wyeth, when Evans’ images are vacant of human presence, a ghostly spirit still haunts the frame. In both artists’ work you can feel the silence. Many of Wyeth’s paintings take place in fall or winter—the colors muted and rustic, the scenes slow, melancholy, and seemingly abandoned. Evans’ photographs are similar, including his portraits. Emotions are not written in the subject’s expression, but in the physicality of their skin, clothing, and hair. In Evans’ Kitchen Corner, Tenant Farmhouse, Hale County, Alabama, 1936, a broom, chair, and clothesline, a lingering tension alludes to an eerie sense of animation. This is a familiar configuration for many of Wyeth’s paintings. However, the fluidity of watercolor paint cannot be replicated in photography, a movement that ignites an emotional connection.

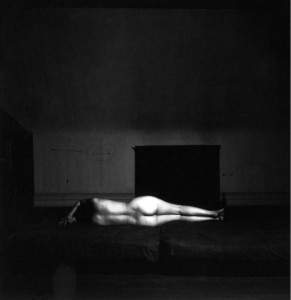

Walking through the exhibition it’s hard not to think about his Helga series, even though it’s not included. Helga’s classically sculpted figure draped on a bed, with her straw colored hair crowned with woven flowers is among his most recognizable work. As I make the connection between photography and Wyeth’s paintings, I imagine Harry Callahan’s wife, Eleanor. Her body’s voluptuous curves—similar to Helga’s—and her rich dark hair and eyes became a fixture in Callahan’s photography. Eleanor, Chicago, 1949, and Wyeth’s Barracoon, 1976, are virtually identical images. Both women lie nude exposing their backside. The light shines on their buttocks illuminating the soft texture of their skin. In front of the women are dark unidentifiable objects that take different forms. In Callahan’s, the shape is visibly rectilinear and opaque. For Wyeth, it’s abstract, murky and ethereal. In each of the foregrounds are lines resembling barbed wire that don’t appear to have any significance to the images other than grounding them compositionally. In many other images of Helga and Eleanor, the women pose nude, illuminated by a single window in the foreground.

When looking at the fluid gestures of watercolor paint, Wyeth’s images become a vague and deceptive memory. His images release the nostalgia of photography from my college classes, and those images of Callahan, Baltz, and Evans embedded in my unconscious. The National Gallery of Art’s Looking Out, Looking In allows the viewer to find a misplaced memory. Wyeth symbolically looks out through the frames of rustic wood of windows and haunting passageways, while we look inward towards our passions.

Looking Out, Looking In is on view until November 14, 2014.