The National Gallery of Art is currently hosting, through June 8, the first retrospective in 25 years of American photographer Garry Winogrand. Upon his death in 1984, Winogrand still had 4,100 film rolls yet to be developed, leaving a great deal of his body of work unseen, and as a result many of the silver gelatin prints in this expansive exhibition are printed posthumously.

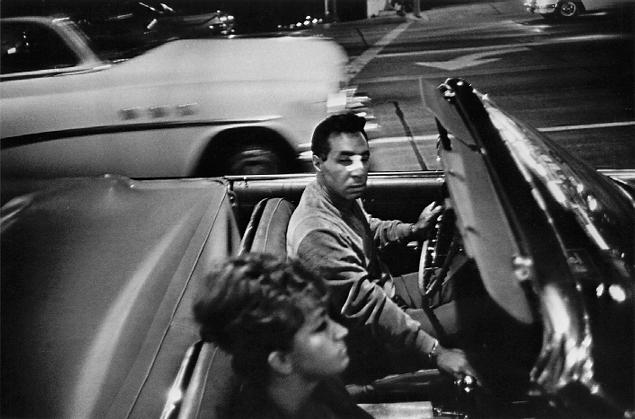

Winogrand’s photographs follow the moments of everyday American life, exhibiting a booming nation of prosperity and “coolness,” while hints of destruction linger in the foreground. He traveled the country capturing both city and suburban lives, combining hope and aspiration with anxiety and instability in mid-century America. There are visions of idealized elegant social happenings like in Metropolitan Opera, that shift to the gritty change in culture, in Los Angeles, 1964, a decade later. His images map a change in American culture between World War II and the insecurities citizens felt during the Vietnam War. Frequently Winogrand’s images emerge as faintly unconscious attempts to impersonate the glamour and sophistication of commercial photography, particularly the photographs he made during the mid-twentieth century.

The retrospective is separated into three sections over seven galleries—each subdivision could function as a distinct exhibition. “Down from the Bronx” offers a glimpse inside his photographs taken in New York City from his start in 1950 to 1971. “A Student of America” is a window into his work made in the same period during exploration outside New York. The final section, “Boom and Bust,” displays a cluster of photographs made during Winogrand’s return to Manhattan where he worked until his death in 1984. These images suggest a consciousness of despair—quite the opposite as seen in his earlier works, where uncertainty and desolation are distracted by a glamorous lifestyle.

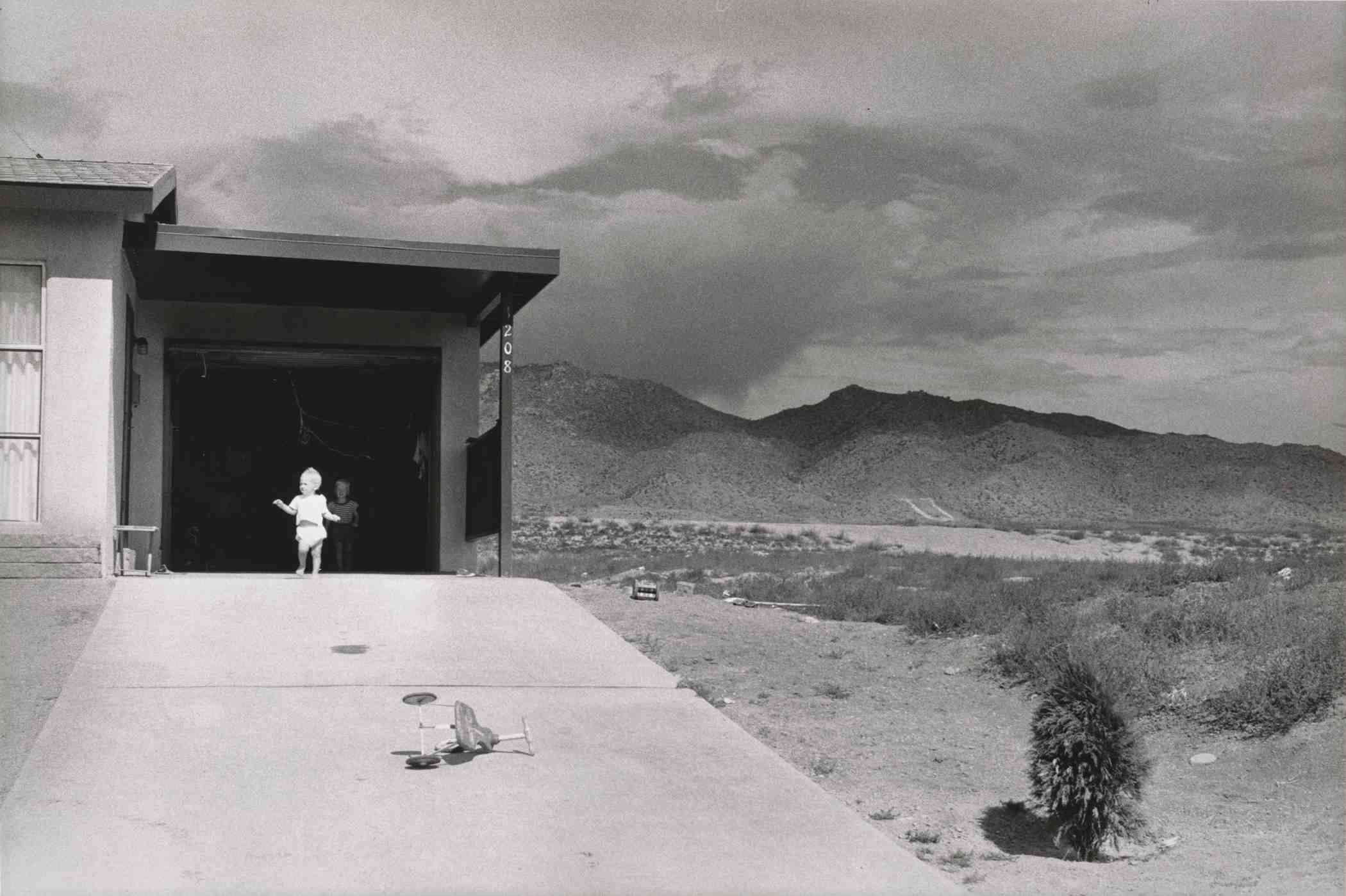

One of my favorites and perhaps Winogrand’s most iconic image is not from New York or Los Angeles but Albuquerque, 1957. It presents a toddler emerging from the black abyss of a suburban garage, with an overturned tricycle in the middle of the driveway. A barren desert receding to a shadowy mountain terrain hugs the house, which draws the viewer’s eye directly to the baby. Gray clouds loom over the horizon, suggesting that there will soon be a catastrophic shift away from an idyllic suburban home. The struggle between suburban prosperity and the tentative nature of the economy feels to be the beating heart in the image. Only faintly behind the child is any indication of parental supervision. The child is alone is his world while his parents are searching for any sort of grasp on security or hope.

Winogrand’s distinctive and rare relationship to the subject is translated to the way the viewer approaches the images. Winogrand does not use a long lens; he steps into his subjects’ realms. The images are small, making the viewer mimic his movement. Unlike many of the photography exhibits at the National Gallery, each photo is given space to stand on its own. Any single image of Winogrand’s is captivating and perplexing—each is one moment that when united with the remaining photographs lace together a lifetime. However, the exhibition is overwhelming. There is so much to look at—one visit isn’t enough. There are many journeys to follow in Winogrand’s photographs, and during each visit a person could follow a completely different road.

Garry Winogrand is on view at the National Gallery of Art until June 8. 6th and Constitution Avenue NW. Monday-Saturday: 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. Sunday: 11 a.m. – 6 p.m.